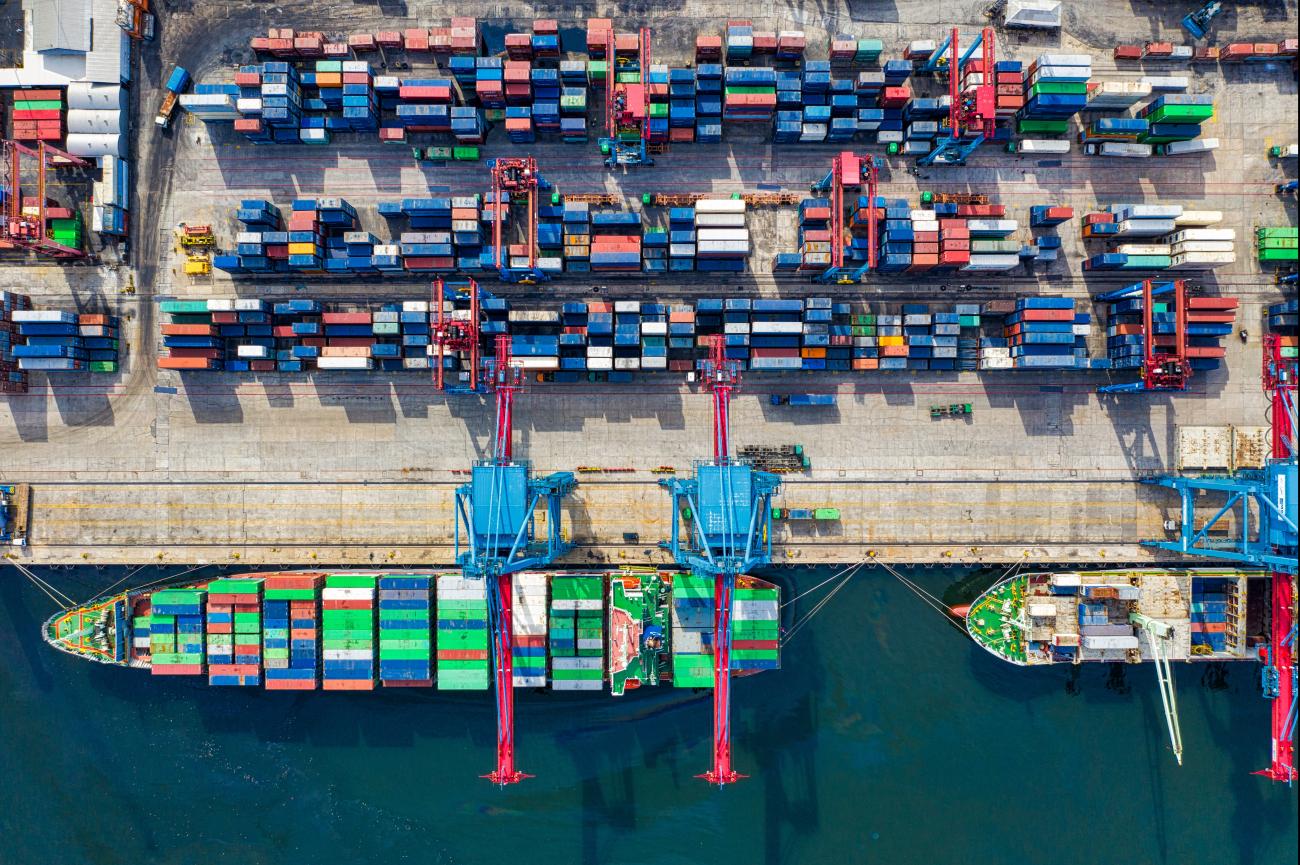

The Suez Canal, a symbol of post-imperialism and a geographical feat of ingenuity, allows for vast flows of economic goods to pass between the east and west without the need to navigate the 3500 miles of choppy waters around the cape of Africa. However, the normally undisturbed journey through the 120-mile artery of trade was choked by a grounded vessel, leaving 12% of world trade that passes through the canal holding its breath. This is just one event in a series of issues that have brought into question the logic of global value chains (GVC’s). This has differed from the nationalist fist-bumping of protectionism, the clean advancement of automation in manufacturing, changing consumer trends and the realisation of supply-side constraints in an age of deep competition (think vaccines). Despite the World Bank’s recent 200-page development report, trumpeting the success of GVC’s, it does leave one wondering if a more nimble and localised system of global production is more appropriate for modern economic demands? Protectionism and automation are the biggest threats to GVC’s at present but a misplaced ship adrift in one of the busiest trade routes doesn’t help.

A GVC is defined as “A global value chain breaks up the production process across countries. Firms specialise in a specific task and do not produce the whole product”. In essence, it is a global division of production that produces components of a larger product. Take a moment to stop reading this ABM insight and think about the device you are using to access this article. It is likely the cobalt used for the lithium-ion battery was extracted in the Congo, the computer chip was manufactured in Taiwan, the screen produced in South Korea, the actual device assembled in China and designed in California. This is a very shallow example, if you were to scale it up by 1000’s of extra suppliers and components, supplying parts for everything from planes, cars and toasters you can begin to grasp the picture of the complexity of global production. Thus, the idea of detangling such a system as integrated as GVC’s is akin to putting a man on the moon or splitting an atom.

The two main benefits of participating in GVC’s is that it allows poorer nations to participate in the global economy and richer nations to benefit from lower consumer prices. Much of the logic for moving production to developing countries is for the relatively cheap labour, thus allowing multi-national companies to keep prices low whilst maintaining strong profit margins. This logic is being challenged by automation and protectionism. Firstly, automation replaces the need for as much low-skilled labour and as a result, prompts firms to question whether there is a reason to produce their goods offshore. Factories once home to progressive movements of social reform and working-class identity, is now home to armies of studded robots carefully assembling dismembered silver parts on a conveyor belt. Automation allows firms to move production onshore and respond to market indicators faster than would have if they had to ship their goods from a factory abroad. Additionally, as consumers increasingly demand better ethical and environmental standards, the pull of automating aspects of production and moving it closer to home grows louder. This is especially relevant as it can be hard for firms to monitor all the activities of their global supply chains. However, there are substantial costs to set up a high-tech factory and there are benefits beyond low labour costs to maintaining production offshore. Warren Bennis humorously speculates, “The factory of the future will have only two employees, a man and a dog. The man is there to feed the dog. The dog will be there to keep the man from touching the equipment.”.

Secondly, protectionism does threaten to destabilise GVC’s. The idea of a global system of firms specialising in a component of a larger product or production process is aimed at keeping costs low and boosting efficiency. Barriers to trade or tariffs risk increasing the cost of components and risk entangling global production in a web of bureaucracy. Proponents of protectionism argue you can bring back jobs and create more local supply chains that support domestic production. There is something to be said for having critical supply chains, like vaccine production or military hardware, closer to home as it is less vulnerable to trade blockages or geopolitics. However, many of the products we use simply would not be affordable if they were to use domestic suppliers or move their production back to the host country. There is increasingly a geopolitical vulnerability to global supply chains, with firms being exposed to sanctions, protectionism and national politics.

Overall, there are risks to global value chains. It can be hard to monitor the environmental standards and ethical work practices of such a global supply chain. Additionally, as we witnessed in the Suez Canal, any disruption to shipping routes can produce large blockages in trade. The main two challenges to GVC’s are protectionism and automation, with the automation making local production more attractive. However, despite the vulnerabilities of trade and global production, the benefits gained through low prices and open markets cannot be replaced.

Written by Henri Willmott, Content Manager